Mali crisis: Key players

It was hit by a coup in March 2012 - and a rebellion in the north that has caused alarm around the world.

The former colonial power has now deployed troops after an appeal from Mali's interim president.

Here is a guide to some of the main players:

The Islamist rebels

The five main Islamists groups in Mali are Ansar Dine, Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (Mujao), al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), the Signed-in-Blood Battalion and the Islamic Movement for Azawad (IMA).

Ansar Dine is seen as a home-grown movement, led by renowned former Tuareg rebel leader Iyad Ag Ghaly.

Its objective is to impose Islamic law across Mali and its full name in Arabic is Harakat Ansar al-Dine, which translates as "movement of defenders of the faith".

In contrast, AQIM - the north African wing of al-Qaeda - has its roots in the bitter Algerian civil war of the early 1990s, but has since evolved to take on a more international Islamist agenda.

It emerged in early 2007, after the feared Algerian Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC) aligned itself with Osama Bin Laden's international network.

The group has since attracted members from Mauritania and Morocco, as well as from within Mali and its neighbours, such as Niger and Senegal.

Idolatry

AQIM says its aim is to spread Islamic law, as well as to liberate Malians from French colonial legacy.

The movement is known for kidnapping Westerners, and ransom money is believed to be a key source of revenue for AQIM, alongside drug-trafficking.

The third Islamist group, Mujao, is an AQIM splinter group, formed in mid-2011.

It says its objective is to spread jihad to West Africa rather than confine itself to the Sahel and Maghreb regions - the main focus of AQIM.

But Mujao's first major operation was in Algeria in October 2011, when it kidnapped three Spanish and Italian aid workers in the town of Tindouf. The hostages were freed in July 2012, reportedly after a ransom was paid.

Although it has many Malian Tuaregs within its ranks, Mujao is believed to be led by a Mauritanian, Hamada Ould Mohamed Kheirou.

Before France launched a military offensive on 11 January 2013 to drive out the militants, Mujao's sphere of influence was mainly in north-eastern Mali, where it controlled key towns such as Kidal and Gao, regarded as the drug centre of Mali.

Ansar Dine's influence was mainly in the north-west, where it captured the historic city of Timbuktu in May 2012.

The group split in January 2013, when the IMA - led by Alghabass Ag Intalla, an influential figure in Kidal - was formed.

Mr Intalla was a high-ranking member of the Ansar Dine team which negotiated with Mali's government until late 2012.

He says he split from Ansar Dine because he opposes "terrorism", and favours dialogue.

The IMA says it champions the cause of the people of northern Mali, who say they have been marginalised by the government based in far-off Bamako since independence in 1960.

AQIM operated freely across the north since its formation in 2007, and helped Ansar Dine and Mujao to seize power of key northern cities in 2012.

Its recruits were said to have been part of the police force which imposed Sharia in Timbuktu.

The Arabic TV channel Al Jazeera reports on its website that its correspondent saw top AQIM commander, the Algerian Abdelmalek Droukdel who is also known as Abu Musab Abdel Wadoud, touring Timbuktu's main market last year.

There are unconfirmed reports that AQIM has also given training in the vast Malian desert to Boko Haram, the Islamist group which has carried out a wave of bombings and assassinations in Nigeria.

The Signed-in-Blood Battalion, led by the Algerian Mokhtar Belmokhtar, also has strong ties with Ansar Dine and Mujao.

It was formed late last year as an AQIM offshoot after Belmokhtar fell out with the group.

According to Mauritania's Sahara Media website, which has strong contacts among the militants, Belmokhtar joined the administration of Gao after it was seized by Mujao.

All these militants follow the Saudi-inspired Wahhabi/Salafi sect of Islam, making them unpopular with most Malian Muslims who belong to the rival Sufi sect.

They have tried to impose their version of Islam, amputating limps of people convicted of crimes and and destroying Sufi shrines, which they claim promote idolatry.

The UN Security Council has warned that that the destruction of shrines in Timbuktu, a world heritage site, could amount to a war crime.

According to a report in India's The Hindu newspaper, Ansar Dine and Mujao have expanded the rebellion beyond the Tuaregs by incorporating a number of other ethnic groups like the Bella and Songhai (who have historically opposed the Tuareg) into a multi-ethnic force, motivated by religious fervour.

The ethnic rebels

The National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (known by its French acronym of MNLA) is ethnically driven, fighting mostly for the rights of Mali's minority Tuareg community.

It was formed by Malian Tuareg in 2011, as a successor to previous rebel groups.

During Col Muammar Gaddafi's rule in Libya, many Malian Tuareg joined his army, in a move that was welcomed by Mali's government to end conflict within its borders.

After Col Gaddafi's overthrow in 2011, they returned to Mali, swelling the ranks of the MNLA as it spearheaded an uprising against the Malian army, in alliance with the Islamists.

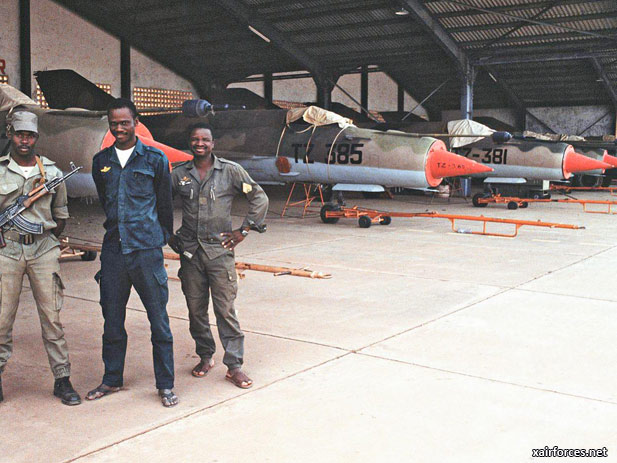

The Tuareg who were in Libya - described by some analysts as an "arms bazaar" - also brought with them weapons, including surface-to-air missiles which the MNLA said it had used to shoot down a Malian Air Force MIG-21 jet in January 2012.

Supporting France

By April of that year the MNLA-led fighters had routed government forces and the group declared the north an independent state, named Azawad.

However, no other country recognised the state, showing the MNLA's isolation in the global arena.

At the same time, its alliance with the Islamists collapsed and Ansar Dine and Mujao drove its forces out of the main northern towns.

Some analysts believe that the MNLA's influence waned after it ran out of money, causing many of its fighters to defect to Ansar Dine and Mujao.

The Islamists are far richer, earning money in recent years by kidnapping Westerners for ransom and trafficking cocaine, marijuana and cigarettes.

The MNLA has come out in support of France's military intervention, hoping that this will help it regain control in the north.

Two important figures in the MNLA are the general secretary Bila Ag Cherif and Mohamed Ag Najim, the head of the movement's military wing.

At the same time, the group has watered down its demand for independence, saying it will settle, as a first step, for autonomy.

Last year, the MNLA endorsed mediation efforts by Burkina Faso to end the Malian conflict.

Ansar Dine - the home-grown Islamist movement - also expressed support for the initiative. It had announced a ceasefire in November to give peace talks a chance.

But in early January, the ceasefire broke as Ansar Dine and the Malian army accused each other of resuming hostilities.

The junta leader

As the rebels were gaining ground in the north in early 2012, Malian soldiers staged a mutiny at the Kati military camp located about 10km (six miles) from the presidential palace in Bamako.

It culminated in a coup, led by a mid-ranking army officer Capt Amadou Sanogo, one of the few officers who did not flee the Kati camp when the rank-and-file soldiers began rioting and then headed for the seat of government.

Having overthrown President Amadou Toumane Toure, he promised that the Malian army would defeat the rebels. But the ill-equipped and divided army was no match for the firepower of the rebels, who tightened their grip over the north in the immediate aftermath of the coup.

Capt Sanogo, who is in his late 30s, is from Segou, Mali's second largest town some 240km (150 miles) north of Bamako, where his father worked as a nurse at Segou's medical centre.

Former Mali-based journalist Martin Vogl describes the army officer as a forceful, confident and charismatic man, friendly but with a slightly abrupt manner.

In the army all his professional life, Capt Sanogo received some of his military training in the US - including intelligence training.

Ironically, Mali was until recently seen as a relative success story in terms of US counter-terrorism efforts.

The US had trained Malian forces to tackle Aqim, but these soldiers - led by Capt Sanogo - staged the coup in Mali.

US Africa Command head, Gen Carter Hamm, has said he is "sorely disappointed" with the conduct of some of the US-trained Malian soldiers.

Some of the elite US-trained units are also said to have defected to the Islamist rebels, who they were originally trained to fight.

Capt Sanogo has since handed power to a handpicked civilian government, but was recently named the head of a committee to oversee reforms in the military and is believed to be paid about $7,800 (£5,250) a month.

The interim president

Dioncounda Traore had long harboured presidential ambitions - but he had hoped to come to power in elections originally scheduled for April 2012.

He was born in 1942 in the garrison town of Kati, just outside of the capital Bamako.

He pursued his higher education in the then Soviet Union, Algeria and France, where he was awarded a doctorate in mathematics.

He returned to Mali to teach at university - before getting involved in politics.

He was a founding member in 1990 of the political party Alliance for Democracy in Mali and between 1992-1997 he held various ministerial portfolios including defence and foreign affairs.

In 2007, he was elected as speaker of the National Assembly.

He was an ally of the deposed President Amadou Toumani Toure, who had become deeply unpopular.

As a consequence, many Malians are wary of Mr Traore, who is not seen as charismatic, says former Bamako-based journalist Martin Vogl.

This boiled over in May 2012, when supporters of the coup attacked Mr Traore in his office, forcing him to seek medical treatment in France.

When Ansar Dine ended its ceasefire and entered the central town of Konna on 10 January, the interim president appealed to France - the former colonial power - for military help.

He declared a state of emergency, arguing that the rebels wanted to expand "criminal activities" across the country.

France agreed to his request, saying it could not allow a "terrorist state" to emerge in Mali.

The ousted president

Amadou Toumani Toure - the army general widely credited with rescuing Mali from military dictatorship and establishing democracy in Mali - fled to Senegal after the March 2012 coup.

At first, forces loyal to him resisted the military junta, but he eventually accepted that his rule was over.

Known as ATT, Mr Toure himself first came to power in a coup in 1991 - overthrowing military ruler Moussa Traore after security forces killed more than 100 pro-democracy demonstrators.

He handed power back to civilian rule the following year - gaining respect and the nickname "soldier of democracy".

He went on to win presidential elections in May 2002, and was re-elected in 2007.

Born in 1948, ATT had no official party - and had always sought the backing of as many political groupings as possible.

His critics repeatedly accused him of being soft on militant Islamists, diverting US-supplied money and weapons to fight the MNLA, whom he saw as a bigger threat.

Analysts doubt that Mali will have another democratically elected president anytime soon.

Foreign powers

At first, the West African regional body, Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas) - of which Mali is a member - spearheaded initiatives to resolve the complex Malian conflict.

Alongside Burkina Faso's mediation effort, it was drawing up plans to send troops to Mali.

But a UN-approved deployment was expected to take place only in September, so that the mediation effort could be given a chance to succeed and troops could be given training.

African leaders did not seem confident that a regional force could win a war against the rebels and appealed for help from Western powers.

In early January, the African Union chairman - Benin's President Thomas Yayi Boni - called for Nato to lead an Afghanistan-styled intervention in Mali.

Of the Western powers, the US was said to be most reluctant to support military action.

In contrast, France was a staunch advocate of intervention soon after the rebels' 2012 gains, but wanted an African force to be in the forefront of battle.

Following the new rebel advance in January this year, France felt it could no longer wait for African troops to be deployed and declared war on the rebels.

Now, Ecowas has started to deploy troops, which are expected to number more than 3,000 troops. Nigeria will form the backbone of the force, contributing 900 soldiers.

Other countries that have pledged troops include Ghana, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso and Niger.

Chad, which is not part of the regional body Ecowas, has also sent a large number of soldiers to work in co-ordination with French troops.

Among North African states, Egypt has condemned France's intervention and has pushed for peace talks to end the conflict.

Algeria was known to have privately argued against military intervention when the idea was first mooted, fearing that the rebels would retreat to its side of the border in the face of a military assault, destabilising its territory even further.

However, it has since changed its position, allowing France to use its air space to launch strikes in northern Mali.

Source: BBC News - 26 March 2013

Photo: The Malian Air Force MIG-21 Fighter Aircrafts (Photo by files)

(26.03.2013)

|